SIGNING THE DECLARATION

OF INDEPENDENCE

You may not want to shoot off all your fireworks on July 4. There are several dates and events that largely been forgotten in the story of America’s independence.

After the French and Indian War (1754 - 1763), relations between Great Britain and the colonies began to sour. Britain had spent a lot of money sending troops to support colonists, primarily in the northeast, whose land claims were being threatened by the French. To recoup its expenses Parliament levied a series of taxes and tariffs on the colonies.

The Stamp Act of 1765 taxed printed paper such as that used for legal documents, books, newspapers, even playing cards. The Townshend Acts of 1767 placed tariffs on glass, lead, paint, paper and tea. In addition, the Quartering Act required colonists to house and feed British soldiers in their private residences.

The last straw came as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, when the Coercive Acts (which Americans called the Intolerable Acts) closed Boston Harbor, increased the Royal Governor’s power, and restructured Massachusetts’ judicial system.

In October 1774 the first Continental Congress sent a Petition of Grievances to King George III, claiming Parliament had no right to tax the colonies without representatives within that body. King George ignored the petition.

Moderate delegates tried reconciliation again in July 1775, sending the king the so-called Olive Branch Petition. Still, no response.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee, a Virginia delegate at the Second Continental Congress, introduced a resolution that "... these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

Though the resolution was generally received favorably, declaring war was a big step. Thus Congress tabled the resolution, calling for a three-week recess so delegates could return home to confer with their constituents. Before adjourning, however, Congress appointed a Committee of Five to draft a statement outlining their justifications for declaring independence.

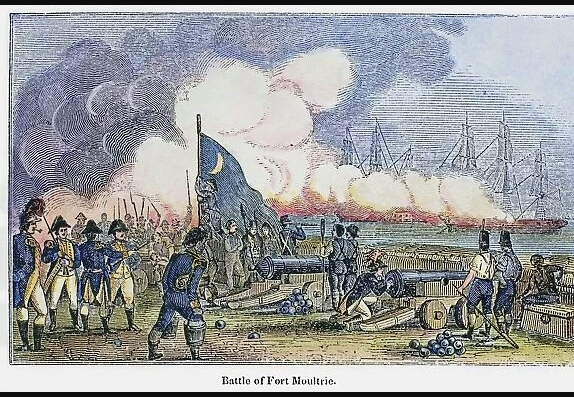

The first draft of the Declaration of Independence was presented to Congress on June 28, 1776, the same day Col. William Moultrie and a small group of poorly armed Carolinians in an unfinished fort on Sullivan’s Island shocked the Western World by defeating nine heavily armed British warships.

On July 1 the reconvened Congress discussed Lee’s resolution for calling for independence. In a straw poll that day, only nine colonies voted in favor of its adoption. New York abstained because they had not heard from their leadership in Albany. Delaware withheld its vote because its two-person delegation was split, one in favor and one opposed. Pennsylvania voted no in the hope that a diplomatic compromise could still be worked out, and South Carolina withheld its approval, suggesting they hold out for a unanimous vote after more discussion.

Indeed, by the next day, July 2, Pennsylvania had been persuaded to change its vote, Edward Rutledge had convinced South Carolina to vote yes as well, and Delaware’s third delegate, Caesar Rodney, galloped on horseback 70 miles overnight through a thunderstorm, arriving just in time to break his colony’s tie in favor of adoption. New York again abstained.

John Adams, a member of the Committee of Five, later wrote that July 2 would go down in history as the date of America’s independence, saying “The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival … from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Likewise that evening the Pennsylvania Evening Post reported: “This day the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS declared the UNITED COLONIES FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES.”

Having now established America’s independence through the Lee Resolution on July 2, Congress next took up approval of the Committee of Five’s Declaration. Over the next two days, delegates fine-tuned a number of changes, including South Carolina’s insistence on deleting language deemed to be critical of slavery.

The Declaration’s final text, outlining the justifications for breaking with Great Britain, was approved by Congress on July 4 and sent to the printer, though with no signatures as of yet. In fact, some of the final signers were not even elected to the Congress until after July 4.

On July 9, New York cast the last vote to adopt the Declaration unanimously. Two weeks later, on Aug. 2, according to Congress’s minutes, “[t]he declaration of independence being engrossed & compared at the table was signed by the Members.” Members who were not present continued to add their signatures once they returned to Congress.

From the beginning, however, Americans have celebrated Independence Day on July 4, the date when the DOI was approved, rather than on July 2, the date when independence was proclaimed.

That said, you might want to save some of your fireworks for July 9 or Aug. 2, if you haven’t already fired them all on July 2.