MARSHLANDS HOUSE

Lawton Plantation once lay along the winding banks of James Island Creek, near what today is the island’s scenic Harborview Road. During and after the Civil War, it was home to Wallace and Cecelia Lawton.

In the years after the war, Cecelia distinguished herself as a savvy businesswoman, buying the Mills House which she renamed and operated as the St. John’s Hotel. She had a number of other assets as well, one of yielded a tidy return on investment.

On the afternoon of Aug. 12, 1901, Cecelia accepted a government check for $50,000 in exchange for Marshlands Plantation, another of her properties on the Cooper River in what we today describe as the Neck Area. The 258-acre site came with a grand house and a few agricultural buildings. Officials also purchased part of neighboring Chicora Park, formerly the Retreat Plantation, for $34,307 from the city of Charleston which had been planning to develop it as a park and golf course. City Council threw in another 760 acres of adjacent marshland for $1.

The transaction was a game-changer for the Lowcountry – for this was the beginning of the Charleston Naval Yard, as it was originally called, the driving economic force for Charleston, and indeed the state, throughout the 20th century. And goodness knows, after the physical and economic devastation of the Civil War, the Great Fire of 1861, Reconstruction, the earthquake of 1886, and a string of powerful hurricanes in the final decades of the 19th century, Charleston desperately needed a new beginning.

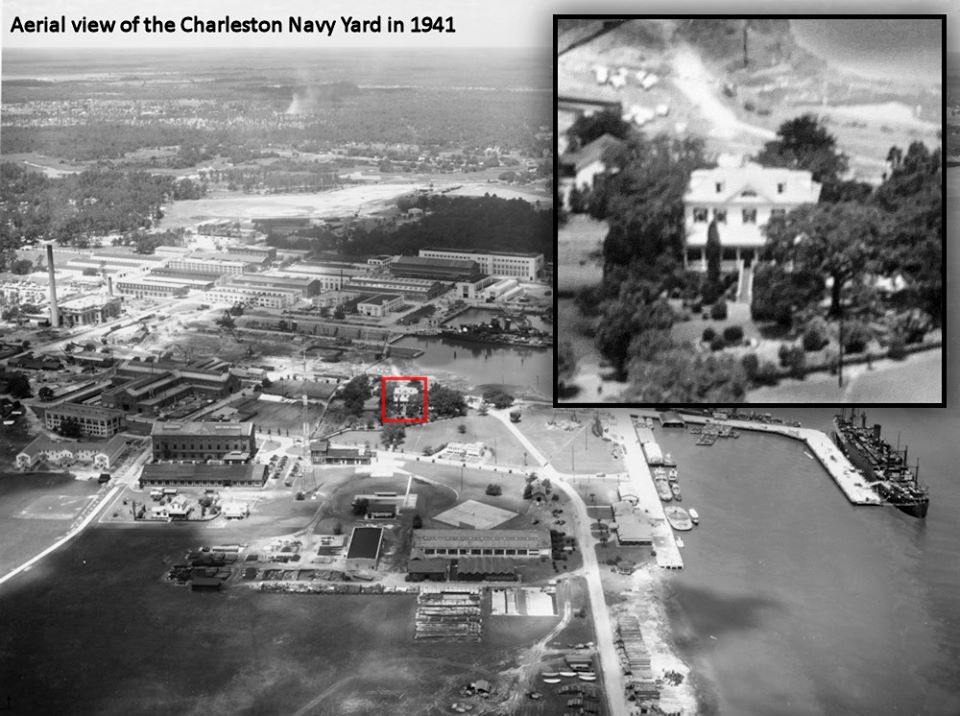

With as many as 26,000 civilian employees during World War II, the base brought more people, higher incomes, and economic stability to the Lowcountry at a time when the rest of the nation was reeling from the Great Depression. At almost the exact center of all this military development sat Marshlands House, sometimes called Lawton House during Cecelia’s ownership.

The Lowcountry’s rice industry had been at its peak in 1810 when John Ball built the two-and-a-half story Federal style clapboard residence. His attention to architectural and interior detailing ensured that the house reflected his wealth and status as a Lowcountry planter. Eight freestanding and two attached columns supported its wide piazza, which sat above a high brick basement. It even had a secret passageway for escape in times of danger.

The house’s nomination to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 noted that its interior “handcarved woodwork is outstanding and especially noteworthy because of the presence of two distinct styles: Adam ornamentation and gouge work,” whereby a craftsman uses a chisel with a curved blade to carve and shape wood designs. Likewise, in his Plantations of the Carolina Low Country, Samuel Gaillard Stoney calls the gougework “lavish and excellently executed” – so fine, in fact, that First Lady Grace Coolidge used images of the Marshlands House interiors when she remodeled the White House in 1925.

A frieze above the east room’s fireplace paid homage to the source of Ball’s wealth, featuring a goddess bearing sheaves of rice and mythical figures holding agricultural tools. The west room’s frieze featured a carving of a Roman tomb.

The gougework on the second floor is simpler, a more indigenous American style that contrasts with the Adamesque details of the first floor. The nomination’s author suggested that perhaps the inaccessibility of Adam mantels due to trade embargoes with Great Britain in 1810 might have influenced the builder’s selection of the simpler carving.

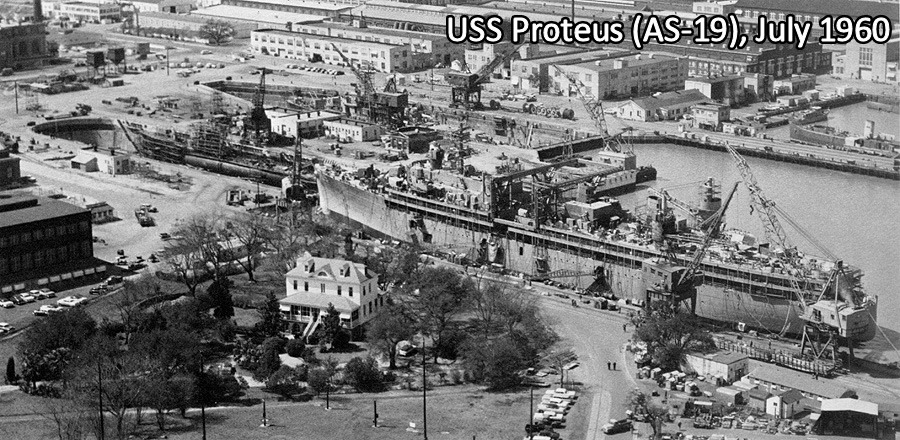

Marshlands House served as officers quarters and administrative offices over the next six decades, as the military’s industrial complex expanded. Gradually, the mansion lost its context as much larger industrial buildings were constructed all around it, soon becoming out of place and scale with the environment it once dominated.

In a July 18, 1961, News and Courier article headlined “Marshlands House May Be Scrapped,” the Navy announced plans to demolish the property to make way for a new dry dock.

Fortunately, a coalition of preservation-minded leaders, including some from private foundations, the City of Charleston, College of Charleston, and Medical University of South Carolina, stepped up to think outside the box about how to save the property. About seven miles outside the box to be exact. They decided to move it.

After dismantling its brick foundation and chimneys, Marshlands House was lifted onto a barge and floated downriver to Fort Johnson on James Island, less than two miles from Cecelia and Wallace’s Lawton plantation. Having been built with superior post-and-beam construction with pegged mortise and tenon joinery, the house made the trip without any structural problems.

Restorers rebuilt its foundation and chimneys, repaired its roof and siding, and reversed 20th century modifications to its piazza. All told, it is nearly the same as John Ball would remember it.

Today Marshland House serves as offices for the S.C. Department of Natural Resources’ Marine Resources Division, which is headquartered at Fort Johnson, and is undergoing another restoration. Though tours of the house’s interior are currently not offered, you can visit the exterior site during weekday business hours and enjoy a fabulous view of Charleston Harbor and the city’s skyline.