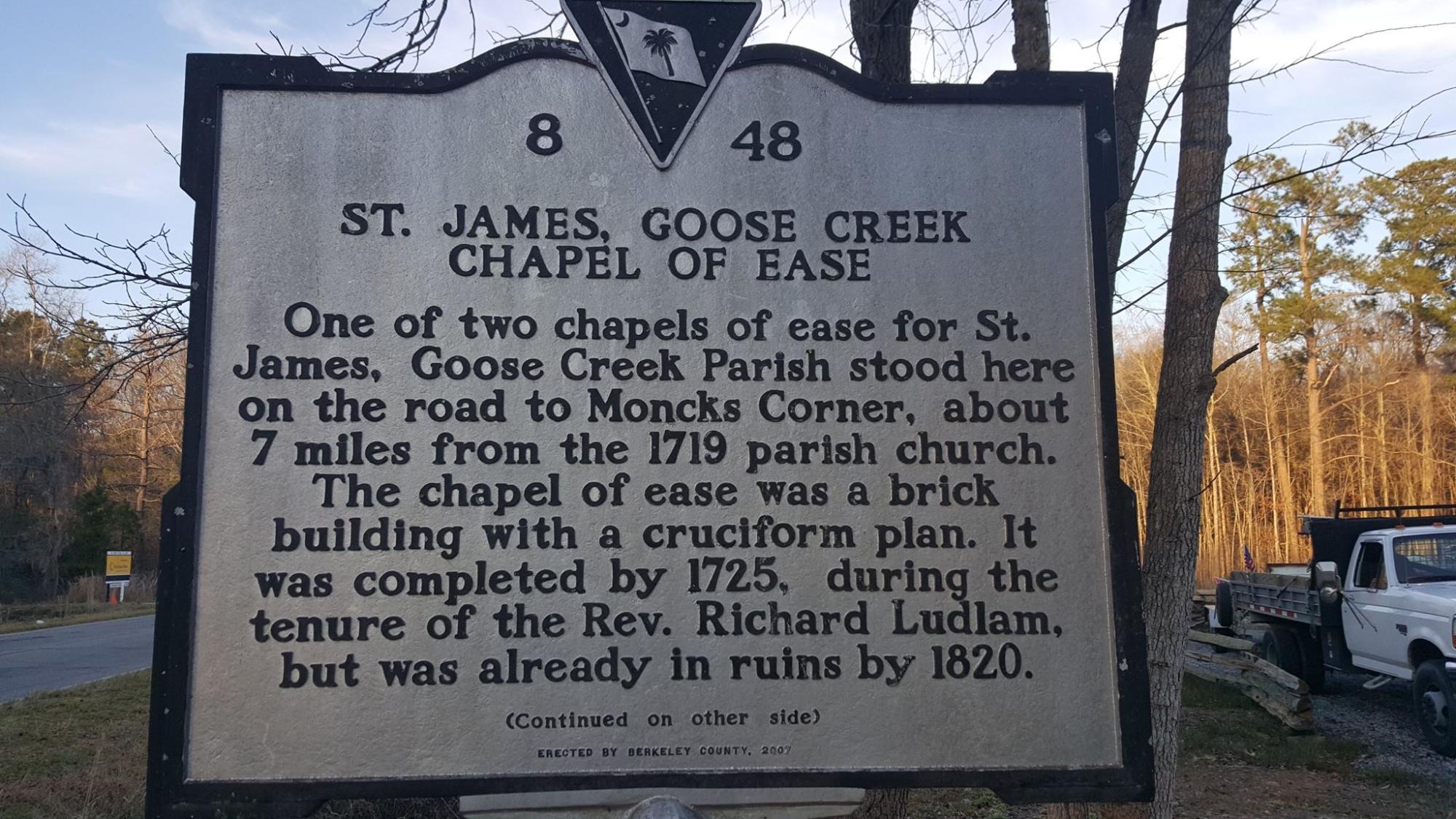

ST. JAMES GOOSE CREEK CHAPEL OF EASE/

BETHLEHEM BAPTIST CHURCH

Perhaps no place else in America tells a more poignant story of our nation's complex history than a small plot of land quietly tucked away along the banks of Chapel Creek in Berkeley County, S.C. Dedicated in 1715 as "sacred ground" by Col. George Chicken, the site has served at various times as a footpath, trade route, campsite, fort, plantation chapel of ease, and a Protestant church. Events that have occurred here vividly tell the stories of indigenous people, colonists, enslaved people, Revolutionary War Patriots, the Lowcountry's great plantation society, and Civil War soldiers - all of whom once lived, worshipped, fought and died here.

The Wassamassaw Baptist Church (also known as Bethlehem Baptist Church) was established here in 1784, built on the site of the former St. James Goose Creek Chapel of Ease.

Innumerable dramas of good and evil emanate from this spot, though decades of neglect have allowed its poignant stories to fade. In 2015, however, a dedicated group of volunteers established a non-profit organization charged with preserving, restoring and sharing the stories of this historical site. (Source: Goose Creek: A Definitive History, Vol. 11, p. 33.)

George Chicken's Camp

One of the Lowcountry’s many special, but virtually forgotten historic places lies amid a small wood tucked between Chapel Creek and old S.C. Highway 52 in Goose Creek. Though today’s commuters zip past its historic highway marker driving to and from Charleston’s urban core, this spot was once a full day’s trek to the city’s colonial wharves.

It reminds us that simple geography plays a huge role in shaping history. Before humans ever lived here, small animals would cross what we call Chapel Creek at its shallowest point, which runs along the edge of this property. Predators followed, tracking smaller prey, and eventually indigenous people began hunting the larger animals.

As winter blossomed into spring and summer, natives migrated from inland hunting grounds to fish along the harbor’s shores, roughly traveling a footpath along what we know as S.C. State Highway 52 to Rivers Avenue, eventually merging into King Street and on down the peninsula.

When Europeans arrived in the 1670s, they traded with natives within the colony’s interior, making Goose Creek the Lowcountry’s formidable frontier of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Ladened pack animals carried imported guns and manufactured items outbound, trudging back piled with deerskins and beaver pelts bound for European markets.

Traders usually walked, reserving the use of their pack animals for the heavy bundles of goods strapped across their backs. Mules and donkeys generally covered about 20 miles a day before they balked, ready to knock off for a graze and evening’s rest. Because of that, traders often stopped along the shallow freshwater creek the evening before crossing over to begin the last 22-mile leg of their journey to Charles Town the next morning. The site came to be known among traders and frontiersmen simply as “the camp.”

One of the traders who frequented this trail was an ambitious young man named George Chicken, who, along with his pack ponies, spent many nights at the campsite. With an entrepreneurial spirit and perhaps tired of the grueling and dangerous life of an Indian trader, Chicken dreamed of becoming a merchant and planter, successfully applying for a small grant of land along the creek on which to build a tavern to accommodate weary traders.

By that time, the colony’s lucrative trade with indigenous people had devolved into the even more lucrative trading of indigenous people. Though not the only colony to enslave natives, Charlestonians were among its most egregious practitioners, exporting men, women and children to the West Indies where they were forced into back-breaking labor on huge sugar plantations. While here natives were familiar with the local landscape and near their families and tribesmen who could help them escape, they could not escape as easily from West Indian island plantations.

Historians have suggested that between Charles Town’s founding in 1670 through the Yemassee War of 1715, more than 50,000 enslaved natives were exported through the colony’s port, many more souls than were imported from West Africa during the same period.

For decades, tethered lines of captured natives languished at Chicken’s camp on the last night of their lives in their homeland, waiting for sunrise to begin the final leg of their dreaded journey to the waiting slave ships in Charles Town’s harbor.

While the sordid slave trading enterprise returned fortunes for Charles Town’s traders and merchants, it also forged more than a dozen of the region’s tribes into a confederacy that would nearly destroy the colony in 1715.

Sources for more information:

Heitzler, Dr. Michael J., Goose Creek: A Definitive History, Vol. II, (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2006)